“If you could kill someone once a year and get away with it, would you?”

This was an anonymous message posted to the app Secret and according to its algorithm, was written by someone I know.

Users were outraged and dismayed at the words, quickly posting comments like “get help” and “what’s wrong with you?!”

I was somewhat reassured by the decibel level, readjusting my social antennae slightly towards some semblance of moral compass. The reactions served as a reminder that oftentimes in social media, communities tend to police themselves.

It got me thinking. Was the writer serious – or was he or she merely taking advantage of the medium to be controversial?

Will we ever really know what kind of friends we have? And what does that say about us? (Am I that messed up too?!)

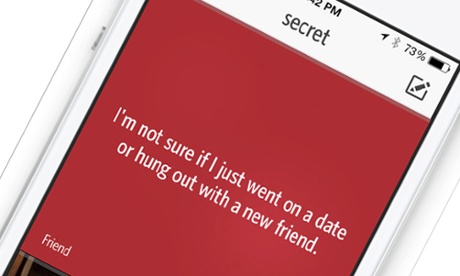

Secret and Whisper are mobile apps that allow users to anonymously post thoughts generally 1-sentence in length. The unmoderated submissions range from from fluffy to business-ish (e.g. Silicon Valley rants and rumours) to the profound. The delight lies in where these topics intersect – a technological venn diagram distributing random missives to the masses.

Twenty years ago at the dawn of the popular internet, anonymity was de rigeur. Digital omnivores created arbitrary handles and sent requests for information only when we could confirm, to the best of our naive ability, that the information sent was heavily encrypted on the receiving side.

With each considering keystroke of our credit card we added a fake layer of security, a counteragent framed of deliberation and trust.

Tap, tap. Tap, tap. I. Am. Trusting. This.

In chatrooms and private messages we reduced our identity to the most basic credentials.

30/f. New York City.

We placed a premium on self-disclosure.

In recent years, these allowances turned a significant corner. Not only did we become eager to share our personal information but we did so in a way to showcase our best possible self. This showmanship comes at a price – there’s no ability to retreat from the real world through anonymous browsing or mutual confession.

Disappearing messages are also of trend. In this model, content disappears after a preselected duration of seconds. Most evidenced is the wild success of SnapChat, who turned down a $3B (yes, billion) offer from Facebook, deciding instead to retain ownership and go forth on their own.

The messaging service was rendered primarily for serving the needs of a typical lowest common denominator, in this case sexting. While the postings aren’t anonymous, their temporal nature provides a semblance of safety since in theory, the content will no longer exist thirty seconds from now.

Online privacy has always been a hotbed issue, and anonymity with some added ephemerality appear to be good partners for communicating in today’s closely monitored world.

Perhaps these expedients serve instead as counteragents; a fallback solution until we discover the real technological lifecycle here.Even if messages allegedly “disappear” or post without provenance, there’s a precedent-setting case waiting to happen if these postings can in fact be tracked. If a threatening message is shared, will the government intervene? Should they?

Given the level of trust in digital security today, it would be little surprise if these messages were not traceable.

After all, when the message is sent, after the tiny bit of information is posted to a server somewhere, ownership is transferred from the creator to the owner along with social currency of unfair supposition. Context is lost and the message becomes subject to whomever has the largest fists and holds its grip the tightest.

Ultimately, who holds the strings?

Let’s again go back twenty years. Let’s say I took a photo (let’s say, just for fun with one of those sassy disposable cameras). I had it developed at the local drugstore and kept the album at home. Would the government have the right to search my house? Would they have the right to search the records from the drugstore without probable cause? And who defines probable cause, if, like my friend who posted on Secret, we’re clearly all a bit nuts?

If secure, tools like Snapchat and Secret enable us to exercise our first amendment rights. We can speak, question, and share freely without running the risk of being held to either substance or context. This goes back to the beginning of the popular internet when it was less about oversharing and more about simply…connecting.

However, this right should be exercised with caution. If you don’t have anything nice to say…it probably shouldn’t be posted at all.